Nightmare Newsletter Vol. VIII: 'Imprint' and the Sins of Our Fathers

Where we take a meandering yet meaningful walk with Takashi Miike straight into the ninth circle of hell and try to crawl our way back out.

[warning: a very old archived post has been released]

One cold dreary night I decided to have a movie marathon in my home, joined by the infamous and well known sicko cinephile, Nikki (@ichithechiller). We’d started indulging in a new tradition in my household that spawned last year, during an unprecedented Saw franchise movie marathon. This turned into a lost evening where five Saw movies were screened back to back with intermittent cigarette breaks to break up the hours of blood spilling and limb dismemberment. It was a rush, and a mind-numbing, confusing mess. It felt like we were clockwork orange-ing ourselves.

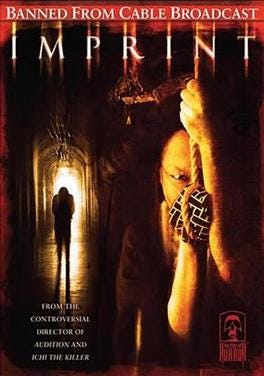

It was also the most fun evening a bunch of brain rotted sickos could have imagined. Recently during another all-night movie marathon, the online wheel spinner generator made up of everyone in the house’s personal picks landed on Takashi Miike’s episode of the anthology show, Masters of Horror, “Imprint.” Now if you already know of this horrid little short film, you’re a real certified sicko.

“Imprint” had a reputation before it ever aired on Showtime. The show creator of Masters of Horror watched “Imprint” and asked Miike to tone down the depictions of violence and other disturbing imagery, but even after edits, Showtime chose not to air it. The episode was eventually released when the series come out on DVD.

Anyone with a morsel of morbid curiosity, yours truly included, would be titillated by that information. The phrase “too disturbing to be shown,” is like catnip to horror fanatics. Hilariously, Takashi Miike thought that American TV censorship would be lax enough for him to fully express himself. "I thought that I was right up to the limit of what American television would tolerate,” said Miike. “As I was making the film I kept checking to make sure that I wasn't going over the line, but I evidently misestimated."

Miike is known for going over the line, dancing on the line, and turning the line into a weapon used to assault the viewer’s eyes. One of my (please don’t roll your eyes) Letterboxd top four films is Miike’s 1999 film, Audition. One day I’ll write a blog post dedicated to how I fell in love with that film. The torture scene in Audition is probably what it’s most infamous for. Miike flaunted his ability to create imagery that’s shocking, stomach turning, and an attack on all your senses. And yet somehow subtle in its own way and artful, not like the torture porn of the American horror scene in the early oughts. If torture scenes in film was a musical genre, Audition was a haunting classical orchestral arrangement by Tchaikovsky, and Saw would be catchy alt rock by a band like Avenged Sevenfold.

But if you think watching Audition can prepare you for “Imprint,” you’d be dead wrong. Miike was inspired by traditional Japanese ghost stories, kaidan. However if they used to tell stories like this back in the day, I don’t know how children ever got any sleep. The tale begins traditionally enough, an American man in Victorian time sails through Japan looking for his lost love, whom he had to leave behind when he returned to America. Now back in Japan, the man searches relentlessly in every town for his love, Komomo, who he wishes to bring back to America with him. Our lead winds up at an island, described as a place where “demons and whores” live. Sounds like my kind of place…

He has no luck finding Komomo on the island, but must spend the night there as there is no way to leave until morning. That’s how our protagonist, played by the incredibly dramatic Billy Drago, ends up in a brothel room with a badly disfigured prostitute who he chose to entertain him for the evening. The prostitute tells the man that she knows what happened to Komomo, and the story she tells devolves into fabrications and madness.

The girl lies and tells protective falsehoods, because the truth is too cruel and painful for the man to hear. Even though we’re not sure we can trust her, hers is the only account we have. She describes her own life, first as the product of a tough environment, a sickly father and a mother who could not raise her on her own. But quickly the veil falls away, and we’re exposed to uglier and uglier truths, her father wasn’t sick, but an alcoholic with a violent temper. He beat her mother relentlessly. Her mother, wasn’t a midwife, but the town’s abortionist, helping all the women abort their babies, extracting the fetuses and tossing them into the local stream, as if they were rotten fish. And mother and father weren’t just lovers but also brother and sister living in isolation because of their relationship. And the local Buddhist monk, was not a comforting paternal presence, but rather a twisted pedophile, who molested her while instilling a diabolical aversion to hell and the path that would lead to it.

Then, somehow, it gets uglier still. Miike at least offers the viewer sumptuous visuals to give the nasty folktale he weaves some kind of temperance. The landscapes are rural, but almost pastoral, there’s pinwheels lining the weedy grass, flaming red hair over tear-streaked faces, and watercolor skies over demonic islands.

Even the most hard to watch scene in the film, a scene where I admit, I watched through my fingers, was shot artfully. Miike is not a man to shy away from what’s painful, and he truly proves that in “Imprint.” The torture scene that the film is most known for unfolds when the lady finally reveals to the Billy Drago what Komomo experienced while she was at the brothel.

Poor Komomo was well liked by men who visited the brothel. She remained optimistic, innocent, and kind, despite her nightmarish circumstances. Unfortunately that was her undoing. The other women in the brothel grew resentful of her, hating her for fantasizing about being loved and rescued, hating her for being liked, hating her for retaining her innocent inner life. When the madam’s precious jade ring goes missing, the other girls don’t hesitate to blame Komomo, and she is no match for their collective hatred. They truss her up in painful shibari, forcing her limbs into unnatural bent back positions. They bring in a woman who specializes in torture (who fun fact, is portrayed by Shimako Iwai, the woman who wrote the story the film was based on). And they’re all gleeful voyeurs as the woman sticks hair pins under Komomo’s fingernails and into her gums, and burns incense into her armpits. After Komomo has been stabbed and burned for hours, she’s left alone, still in an upside down hanging position, with seemingly no end to her suffering.

The scene itself is a stomach turning five minutes long. I could literally feel my guts twist themselves into a knot, while watching. But I couldn’t deny that there was something cathartic in bearing witness as well. It was as if the oftentimes unbearable pain of how women are treated in this world was being turned over, belly up, inside out, and offered up to the screen, totally uncensored.

The ugliness that the female narrator bemoans scarred hers from the time she was born, stained her life from the moment she was conceived, due to her parents being brother and sister—that ugliness—was inevitable. So much of life is walking through different rooms, putting on different faces for the people around you so that you can be useful to them in the function that you’re meant to serve them. Whether it be at a job, or as a daughter, or mother, or customer, or subway rider, we walk through life hiding the ugliness inflicted on us or within us. In ‘Imprint’, Miike makes that impossible. He lays bare the disgusting, the revolting, the horrible, and the tragedies of life and asks you to look. And if your stomach turns, good, that means you’re still human.

“I can stand any kind of cruelty, but what I can’t take is kindness,” says our lady storyteller. It’s an admission that struck me to the bone. It rings a similar tune to a very commonly repeated line from another very popular movie about prostitution, Pretty Woman, where Julia Roberts’ Vivian says “people put you down enough, you start to believe it… The bad stuff is easier to believe. You ever notice that?” Sex work is what many people refer to as the oldest profession. Men have for centuries subjugated women for their own uses and pleasures. What is that gnawing feeling inside that whispers I’m no good… I’m rotten… I’m worthless…? Some people trace it back to a religious upbringing and a God gifted sense of guilt and shame. Some trace it to their ancestors surviving under unimaginable traumas and carrying that down the bloodline. Some trace it back to an unpleasant memory of childhood. No matter where it came from that gnawing whisper lives inside almost everyone. And any hint from the external world that what it whispers may be true is swallowed and digested without any effort. And so experiencing kindness, or an act of dignity extended to you can feel unbearable. It is antithesis to that whisper inside. It does not align with the deep core belief of worthlessness.

“Imprint” is not just controversial for its vulgar gruesome content, but also for something Miike has been often accused of—a misogynistic portrayal of women. This film and other works of Miike’s like Audition could certainly be viewed that way. Plainly put, there’s scenes of extreme violence against women. However, take a step outside, you can see scenes of violence against women right in the public spaces near the safety of your home. If you opened TikTok, you might have been inundated with videos and stories of women being punched in the face in random acts of violence. These stories are much more disturbing than anything Miike’s imagination could conjure to screen.

The misogyny of the world is so dark and deep. Miike’s choice to show the extremes of women’s experiences is something that I found relief in. I’m not alone in that understanding. Some other great writing online has explored “Imprint” in the context of its portrayal of misogyny. William Leung wrote in Misogyny as radical commentary — Rashomon retold in Takashi Miike’s Masters of Horror: Imprint, “it not only introduces us to a whore who is completely innocent but also proceeds to ask who and what are responsible for making women like her feel guilty about themselves. If my interpretation is correct, then Imprint as a horror film may be said to address a specifically female experience of horror. It shows that what’s “really scary” — more so than imaginary phantoms, demons and bogeymen — is the reality of male control and subjugation of women. To reinstate Iwai’s original question: what if women find that they have “no place to escape”? Short of killing herself, what could a woman subjected to male exploitation do to act “right” in the eyes of men?”

A simple tale, like a man searching for his lost love, intent on rescuing her with his devotion can be a minefield of resonance for the misogyny in this world. “Imprint” does feel like a bedtime story, much like the fairytales we were read as children. Those stories seemed simple, yet were mired in so many dark implications about the values of the human beings who told these stories over and over through the centuries.

“Imprint” is more than a beautifully shot horror short. It’s a text that’s rich for interpretation. Although the film does not comment outright on its white male protagonist who tours an Asian country for sex and expects to save this foreign woman with his love and immigration to America (hmm… does that sound vaguely familiar?), I believe its ending absolves the film from being relegated as just misogynistic torture porn. Billy Drago’s character is a someone we’re familiar with. Legions of men like him have existed throughout history— American soldiers who were stationed in Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines… we don’t even have time to run down the comprehensive history. Ask around most of the wasians you know, most of them have fathers who were in the military…

This male fantasy of traveling to a foreign less civilized land and saving the savage woman and taming her to become your willing servant is a fantasy as old as time. Billy Drago’s character in “Imprint” emphasizes his love for Komomo and his devotion to her. It’s meant to be romantic. But how well does he know Komomo? He can’t tell us much about her besides her disposition and the promises that he made her. She’s a fantasy, a projection, of his own desires and his need to prove that he’s a good man. At the end of the day, the journey, the search, it’s all about him. Komomo is merely a tool for him to use to assuage his guilt.

The phrase “oxford study” is thrown around a lot lately. It was a study that examined interracial relationships between white men and Asian women as seen in media. A Pew Research study that examined real population data on marriages found that the number of Asian women in interracial marraiges have actually been declining. However, this brought me back to the thoughts I had while watching Killers of the Flower Moon, why do we cast blame and shame on the women in interracial relationships and fail to examine the historical context for these relationships? Who has historically held the power in these relationships? Who has historically initiated and pursued these relationship? How can a subjugated woman be at the same time a temptress race traitor and also a submissive mindless sex drone?

Billy Drago’s character in “Imprint” is promptly punished for his fantasies. His dreams of Komomo’s purity and his hope of being a savior are thrown in face by the end of the film. He is no hero. He is not even the narrator or protagonist of this story. He is just man exposed for the selfish misogynistic motivations and drives that laid under his every word. In the end there is no happily ever after that ends in a marriage that saves the woman from suffering. Instead, Billy Drago’s character, unable to face the ugly truth that his hopes are pointless and that he will not be redeemed by saving Komomo, kills the woman who dashes these hopes. He’s imprisoned for his crime, and spends the rest of his life haunted by the women he failed. So maybe a woman’s real chance at justice in this fucked up world is to become an onryō (or vengeful spirit) and haunt and guilt the people who had made the world this way.